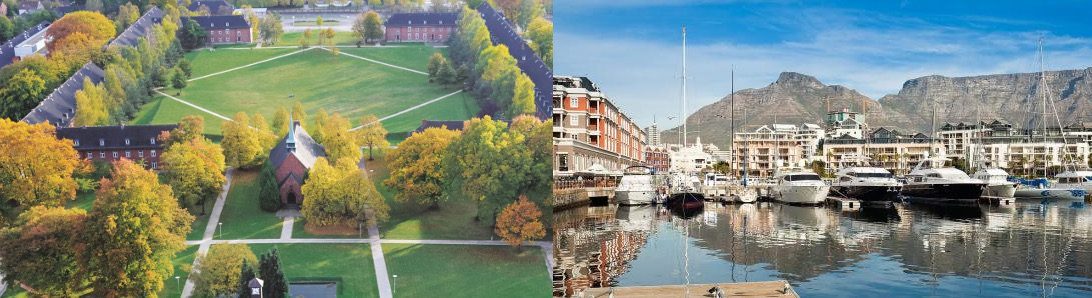

The Wealth Data Science Summer/Winter School (WeDSS) will take place July 1-12, 2024 on two campuses at Constructor University in Bremen, Germany, and the African Center of Excellence for Inequality Research (ACEIR) at the University of Cape Town, South Africa. Both campuses will form a joint online campus for lectures, project work, and exchange. Most projects will take place in Bremen, and one project in Cape Town.

So, it is a Summer School (Germany) and a Winter School (South Africa)!

Read more about the topic below.

Learn more about our research incubator concept and look at our experts and research projects.

Organizers: Hilke Brockmann, Jan Lorenz, Murray Leibrandt, Vimal Ranchhod

Topic: Wealth

Global wealth was “largely immune” to the pandemic and reached a “record high of USD 79,952” per capita in 2020 (Shorrocks et al., 2021). But the distribution is highly uneven (Piketty, 2014). While a small number of individuals possess staggering levels of property, public wealth dropped (Chancel et al., 2021), polarized societies emerged (McCarty et al., 2016), and natural environments deteriorated (Knight et al., 2017).

The link between wealth accumulation and social and environmental degradation is still not well understood. In large part, this is a data problem. Even if the quality and availability of wealth data have substantially improved (Killewald et al., 2017), wealth data remains incomplete and biased. Standard survey methodologies are too costly for many areas of the world and typically fail to capture the super-rich. Tax records are difficult to obtain and do not collect all components of wealth (Vermeulen, 2016).

This is the starting point of our proposal for a summer school. We want to follow the digital footprints of the rich in order to document where, when, how, and why they produce and reproduce wealth. As avid consumers, travelers, and social media users, the wealthy often leave a thick data trail that we will leverage for our purposes (Barros & Wilk, 2021). We will also test if digital data is a meaningful supplement to standard established data sources for wealth and inequality researchers all over the world. The global perspective is important. The concentration of (financial) wealth is an international phenomenon. However, poorer countries often lack the means to maintain an expensive data infrastructure to follow up on this trend. But since multi-purpose information and communication technologies (ICTs) affect all people’s lives (digital transformation), digital data may allow us to better compare wealth across developed and developing countries as well as across social groups.

The aim of our summer school is to make progress on both, data and analysis. Digital data has high volume, velocity and variety and is best analyzed with data science methods. Thus, we propose a “Wealth Data Science Summer School” (WeDSSS). We intend to apply innovative methods to develop and improve theories of wealth generation. We will also store our data in a data lake that will be open for public use after the school has ended. Our school has three

substantive foci which all contribute to a more profound understanding of the genesis of wealth:

- Mechanisms for the Production of Different Wealth Classes e.g. Innovation, Property Rights, Norms

- Mechanisms for the Reproduction of Wealth e.g. Families, Geographies

- Mechanisms for the Redistribution of Wealth e.g. Taxes, Transfers, Patronage

Mechanisms for the Production of Wealth

In economics, wealth refers to the market value of the assets held by individuals, including real, financial, and human capital. Various economists since Adam Smith have identified economic growth as a key contributing factor to wealth creation, and technological progress, in turn, as a key ingredient to growth (e.g. (Schumpeter, 1983) (Romer, 1986) (Lucas, 1988)): innovators can win monopoly rents especially when their innovations are protected by intellectual property rights (i.e. patents, copyrights, trademarks). Not surprisingly, high-tech entrepreneurs and other individuals who can make use of ICTs technologies in winner-take-all economies (e.g. superstars in sports, film, finance, etc.) make it to the top of the global rich lists.

Wealth is hard to assess if assets are illiquid and market value is difficult to determine. This can be particularly relevant in many developing countries, where land is sometimes held in communal trusts and may not be divided or sold by individuals. In addition, large informal settlements provide housing to millions of people but do not have formal title deeds and ownership is often not legally recognized. South Africa is no different, and these limited property rights are overwhelmingly present in relatively impoverished areas.

Thus, in analyzing inequality in wealth across the entire distribution, especially in developing countries, one needs to consider the economic value of the assets that people have access to. This has led to considerable attention being devoted in development economics to the technically and conceptually accurate derivation of asset indices (Wittenberg & Leibbrandt, 2017). In this distinction between access and ownership, it remains important to understand

the power relations that govern the de facto use of these assets as these use rights and norms underpin poverty traps and gendered limitations on the realization of opportunities.

Moreover, for the urban middle classes and old elites, even in developing countries, more conventional measures of wealth are more appropriate. Here, the primary sources of wealth holdings will be in the form of housing, pension fund values, and investment portfolios (Pfeffer & Waitkus, 2021). For the ultra-wealthy, however, measuring wealth and the dynamics that go with it again becomes rather complicated. Social and political capital can be bought and

sold, even though they are difficult to quantify. Secondly, influence and the control of organizations can be established without outright ownership, and these forms of control can be extremely lucrative for individuals. Finally, the ultra-wealthy typically become members of global elites, which makes their wealth holdings and influence even more opaque (Brockmann et al., 2021).

Mechanisms for the Reproduction of Wealth

Wealth tends to accumulate over time. After WW II, for instance, many people in Western societies have accumulated considerable assets which are now gradually handed down to heirs and heiresses (Westemeier et al., 2016). Inheritances are typically skewed – a happy few inherit a fortune while the large majority inherits little to nothing (Baresel et al., 2021). Inheritances mainly happen within families. Yet, family networks and demographics have profoundly changed during the last decades – fertility and marriage rates dropped, divorce rates increased, and new patch-work families emerged. We expect novel insights into the intergenerational dynamics of the reproduction of wealth with a focus on inheritances.

Recent work has also used location to demonstrate spatial accumulation or clustering – with its strong association to housing, schooling, healthcare and communities of a certain quality – as an indicator of the intersecting advantages that are opened up to those who have access to wealth (Chetty & Hendren, 2018). Those born in different locations and with different wealth face fundamentally more enriched or more limited life chances and trajectories.

Similar work in developing country contexts has focused on the role of wealth and assets in underpinning poverty traps and gendered opportunity sets (Barrett & Carter, 2013). Longitudinal and triangulated big data sources i.e. African and European panel data, historical data sets as well as spatial information i.e. satellite images allow to trace people across generations, across family formations, and across space. Through these strong lenses we may

better identify the temporal and spatial accumulative mechanisms under which wealth is reproduced and not as Becker and Tomes (1986, p. S1) predicted: “Almost all the earnings advantages or disadvantages of ancestors are wiped out in three generations”.

Mechanisms for the Redistribution of Wealth

Markets’ and families’ wealth depend on laws – tax laws, property laws – purported and enforced by states. International comparisons reveal stark differences in wealth inequality within countries. The most unequal countries of the world are located in the Global South. The highest GINI coefficient on wealth inequality is determined for South Africa, where the richest 1% of the population possesses 63% of the total national wealth (World Bank, 2022).

Middle Eastern and North African States (MENA) marks the most unequal wealth region of the globe (Chancel et al., 2021).

A different measure of global inequality is obtained by considering the inequality in wealth between countries. Here, the primary drivers of inequality are obtained by comparing measures of wealth across states, where the divide between the Global North and Global South become far more apparent. These can be done at the level of the state, or in a per capita sense, which adjusts for the size of the country and thus implicitly controls for the fact that

large countries tend to have larger wealth holdings and smaller families.

A third way to conceptualize global wealth inequality is to ignore location, citizenship, and statehood; and imagine that each individual is simply a member of a global population of humans. This is analogous to the work on the global income distribution that has been popularized by Branko Milanovich (2012). This approach has the advantage of incorporating both the within-country and between-country variation, while not having to address some of the complexities that arise due to countries having very different sizes. A global analysis of redistributive mechanisms of wealth cannot simply apply frameworks and typologies that have been only based on income data from northern developed countries.

Instead, we can make use new tax data (Genschel & Seelkopf, 2022) (Limberg & Seelkopf, 2022), add information on corruption, housing and welfare policies, and link institutional layers to established wealth surveys and other individual wealth measures in order to understand the local and global mechanisms of wealth preservation better (e.g. Lorenz et al., 2013).

References

Baresel, K., Eulitz, H., Fachinger, U., Grabka, M. M., Halbmeier, C., Künemund, H., Lozano Alcántara, A., & Vogel, C. (2021). Hälfte aller Erbschaften und Schenkungen geht an die reichsten zehn Prozent aller Begünstigten. DIW Wochenbericht. https://doi.org/10.18723/DIW_WB:2021-5-1

Barrett, C. B., & Carter, M. R. (2013). The Economics of Poverty Traps and Persistent Poverty: Empirical and Policy Implications. Journal of Development Studies, 49(7), 976–990. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2013.785527

Barros, B., & Wilk, R. (2021). The outsized carbon footprints of the super-rich. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 17(1), 316–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2021.1949847

Becker, G. S., & Tomes, N. (1986). Human Capital and the Rise and Fall of Families. Journal of Labor Economics, 4(3), S1–S39.

Brockmann, H., Drews, W., & Torpey, J. (2021). A class for itself? On the worldviews of the new tech elite. PLOS ONE, 16(1), e0244071. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244071

Chancel, L., Piketty, T., Saez, E., & Zucman, G. (2021). World Inequality Report 2022. World Inequality Lab.

Chetty, R., & Hendren, N. (2018). The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility I: Childhood Exposure Effects*. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(3), 1107–1162. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjy007

Genschel, P., & Seelkopf, L. (Eds.). (2022). Global taxation: How modern taxes conquered the world. Oxford University Press.

Killewald, A., Pfeffer, F. T., & Schachner, J. N. (2017). Wealth Inequality and Accumulation. Annual Review of Sociology, 43(1), 379–404. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053331

Knight, K. W., Schor, J. B., & Jorgenson, A. K. (2017). Wealth Inequality and Carbon Emissions in Highincome Countries. Social Currents, 4(5), 403–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329496517704872

Limberg, J., & Seelkopf, L. (2022). The historical origins of wealth taxation. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(5), 670–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1992486

Lorenz, J., Paetzel, F., & Schweitzer, F. (2013). Redistribution Spurs Growth by Using a Portfolio Effect on Risky Human Capital. PLoS ONE, 8(2), e54904. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054904

Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7

McCarty, N. M., Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2016). Polarized America: The dance of ideology and unequal riches (Second edition). MIT Press.

Milanović, B. (2012). The haves and the have-nots: A brief and idiosyncratic history of global inequality (Paperback first published in 2012 by Basic Books). Basic Books, a member of the Perseus Books Group.

Pfeffer, F. T., & Waitkus, N. (2021). The Wealth Inequality of Nations. American Sociological Review, 86(4), 567–602. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031224211027800

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth. Journal of Political Economy, 94(5), 1002–1037. https://doi.org/10.1086/261420

Schumpeter, J. A. (1983). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. Transaction Books.

Shorrocks, A., Davies, J., & Lluberas, R. (2021). Global Wealth Report 2021. Credit Suisse.

Vermeulen, P. (2016). Estimating the Top Tail of the Wealth Distribution. American Economic Review, 106(5), 646–650. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20161021

Westemeier, C., Tiefensee, A., & Grabka, M. M. (2016). Inheritances in Europe: High earners reap the most benefits. DIW Economic Bulletin, 6(16/17), 185–195.

Wittenberg, M., & Leibbrandt, M. (2017). Measuring Inequality by Asset Indices: A General Approach with Application to South Africa. Review of Income and Wealth, 63(4), 706–730. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12286

World Bank. (2022). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?end=2014&locations=ZA&start=2006&view=map